LES ANNÉES TRENTE SOIXANTE DIX

HISTORY

Written by Massimiliano Mocchia di Coggiola

Happy clients at the Rainbow Room restaurant, Big Biba, London.

The fluctuations of fashion, as we know, follow mysterious and indecipherable patterns for the average mortal. What generally surprises us are the repetitive returns of certain trends and styles that were in vogue decades earlier. These resurgences can be sparked by a film, a designer, or even a particular way of perceiving and interpreting the world around us through the distorting lens of the present. This lens convinces us that we share a special kinship with the people of a past era—often, thanks to or because of the interpretations of historians focused on that period. But how can we explain the fact that the revival of the past is always undertaken by a society that never actually lived through it?

In the 1970s (and briefly into the early 1980s), there emerged a revival of 1930s fashion, especially in England, France, and Italy. Naturally, this revival was reimagined according to the new stylistic norms of the time. The 1970s represented one of the last flamboyant, baroque periods in fashion. This applied not only to women’s fashion but, perhaps even more so, to men’s fashion. As a renowned tailoring expert once said, “The order was Corinthian.” Exaggerated jacket lapels, pagoda shoulders, tightly cinched waists and hips, fitted trousers that flared dramatically at the bottom to give the figure more movement and, in a way, balance. These stylistic elements were reminiscent of the 1930s, though they were reinterpreted in an almost caricature-like way as they came back into vogue.

But why Corinthian? This term refers to the final and most elaborate order of Greek capitals, the most ornate and whimsical of the three classical styles, following the Doric (very minimal) and the Ionic (somewhere in between). When one looks at men’s fashion of the 1950s and 1960s, one can understand what I mean by this comparison.

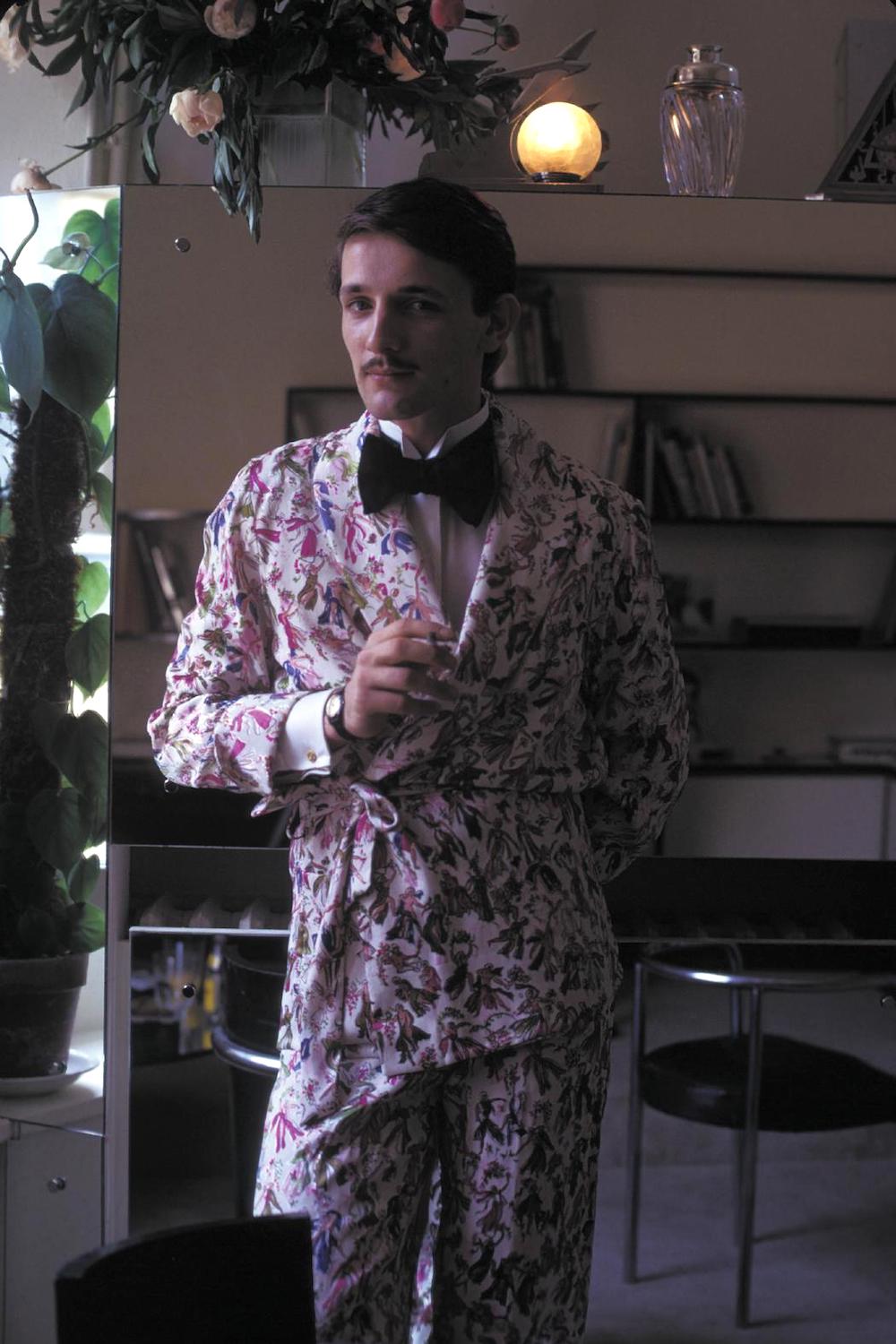

Jacques de Bascher, Vogue 1973, photographed by Alex Chatelain.

Much can be said about the “disco” style, a fashion movement with no shortage of detractors. Conservative gentlemen of the English sartorial tradition identify the 1970s and early 1980s as the absolute nadir of men’s fashion—a decade that, in their eyes, achieved “excesses of all kinds.” Such remarks have been made by men whose youth predates the 1970s, such as Giovanni Nuvoletti, or by individuals who, by 1978, were more inclined to switch their allegiances than to care about the color of their jacket. These criticisms, therefore, hardly seem to reflect the true spirit of the decade in question.

The 1970s were not merely a chaotic jumble of absurd bell-bottom pants, corduroy, floral Lycra shirts, big hair and mustaches, guitars, and joints. Of course, the hippies were there. But alongside this countercultural explosion, there existed an elegant and particularly refined side to the decade, characterized by luxurious materials and exquisite tailoring. This was accompanied by a way of thinking about men’s fashion that adhered to traditional values while remaining innovative. This modus vivendi exhaled its final breaths precisely in this colorful decade. And as the old icons of past dandyism were truly fading away, new gentlemen of style began to emerge in the pages of magazines, visibly inspired by the masters of the past.

“understatement in flamboyance”

For once, fashion magazines kept pace with the times: photographers of varying renown—Barry McKinley, Helmut Newton, Chris von Wangenheim, David Bailey, among others—set out to create images of a beauty that was equal parts camp and provocative. Alongside top models like Pat Cleveland and Jerry Hall, dressed as though they’d indulged in cocaine and LSD on the set of a pre-Code Hollywood film, appeared slim, dandyish men squeezed into double-breasted blazers with enormous lapels, choked by oversized velvet bow ties, crouching to paint their companions’ toenails or serving as a desk for an aggressive, eyebrow-less blonde.

The tasteful man of the 1970s steered clear of the more traumatic trends of the era: lace-front shirts (sometimes edged in black!), synthetic-fiber suits, or python platform boots complete with goldfish swimming in their transparent soles. These dandies navigated the chaos of 1970s fashion with discernment, selecting the best the era’s marketplace had to offer. The photos accompanying this article aim to illustrate the peculiar golden rule that seemed to guide the men of taste during this time: “understatement in flamboyance.”

This “1930's seen through the 1970's ” Art Deco era was, in essence, a splendid greenhouse, capable of reviving a certain Wildean aestheticism: refinement and elegance with a touch of eccentricity, both allowed and celebrated. Vulgarity, already absorbed and digested during the preceding decade, was now accepted as a humorous citation—a playful nod to American pop culture. The precious taste typical of these gentlemen once again illuminated men’s sartorial fantasies, before quietly fading away by the mid-1980s. A few names remain legendary: Tom Gilbert, Doug Hayway, and Tommy Nutter, the London tailors who invented a style that was both new and “vintage” at the same time. The refined figures of the era included Cecil Beaton, Peter Coats, Jacques de Bascher, and Antonio Lopez. In France, designers such as Yves Saint Laurent—and especially Karl Lagerfeld, who famously dined in formal evening dress at La Coupole, a 1930s restaurant—alongside Manolo Blahnik, proudly represented this eccentric yet sophisticated style.

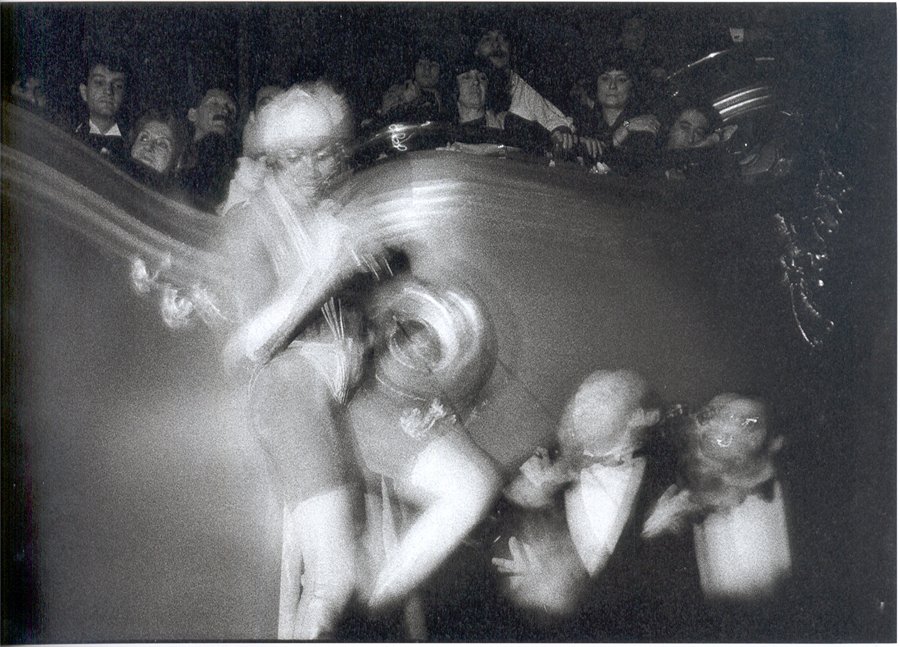

The music world, too, could not resist the pull of vintage. The tuxedo made a triumphant return at soirées held at Paris’s Palace and New York’s Studio 54—disco temples where entire nights were sacrificed at the altar of glamour. At the Palace, the resident DJ, Guy Cuevas, was photographed wearing a monocle and white tuxedo, channeling Erich von Stroheim, while the most fashionable singers embraced the big band aesthetic for their public appearances. Think of Barry White’s Love Unlimited Orchestra or the disco-jazz compositions of the Alessi Brothers, such as their hit “Oh, Lori.”

Reading the ever-growing memoirs of the protagonists of this era, one realizes that the vintage craze was initially fueled by a popular trend: in nightclubs, alongside the cultural icons of the time, there thrived an underworld of nocturnal creatures eager to stand out. Entry to places like Le Sept, the Palace, or Les Bains-Douches was strictly controlled by blasé gatekeepers who only let in the best-dressed—or the most outlandishly dressed. In short, those who gave the impression they had come dressed for a special occasion and not just by chance. These gatekeepers merely obeyed the diktats of nightlife royalty, such as Fabrice Emaer, who famously declared that at the Palace, only the well-dressed had a place.

Much like a court gathering at Versailles under Louis XIV, the courtiers of the night developed a taste for elaborate attire—albeit often without a penny to their name. How did they manage? Paris’s legendary second-hand shops came to their rescue. In the 1970s and 1980s, thrift stores were still brimming with their fathers’ old suits, as well as tails, tuxedos, and other treasures from the early 20th century. It was effortless to reclaim these garments and reinterpret them with a fashion-forward twist.

Evenings at Le Palace.

In sum, the references were not strictly confined to the 1930s. The embrace of vintage fashion extended to men’s styles spanning from 1900 to 1940. The wardrobe of the modern gentleman aligned perfectly with the broader rediscovery of Belle Époque Parisian restaurant décor—hidden away during the 1950s and 1960s as “outdated” and brought back to light through the work of designer Slavik—Art Deco (the “1925 style”), William Morris-inspired hippie tunics, and what the world of cinema was beginning to portray.

Cinema, in particular, quickly appropriated this new trend: a host of films starring Helmut Berger (Salon Kitty chief among them) or Liza Minnelli (Cabaret) resonated deeply with the era. But it is essential to also mention Bertolucci’s The Conformist, the precursor of this international fashion movement, which established a true aesthetic paradigm. It inspired a wave of “costumed” films, such as Pretty Baby, The Boyfriend, Valentino, The Damned, Farewell, My Lovely, Chinatown, Lucky Lady, The Sting, White Mischief, the Poirot series starring Peter Ustinov, and, of course, The Great Gatsby (with costumes designed by Ralph Lauren, the epitome of 1930s-seen-by-the-1970s chic).

This fashion trend was destined to have a relatively short lifespan—a natural limitation given the finite pool of references from which it could draw. The arrival of AIDS decimated much of the generation that had championed luxury, carefree living, and the exuberant joie de vivre of the era. But the symbolic death knell came on July 12, 1979, at Chicago’s Comiskey Park, where a crowd of 50,000 gathered to burn disco vinyl records—a pyre that went down in music history as “Disco Demolition Night.” Too gay, too superficial, too aestheticized—the fashion that had accompanied the kitsch, uninhibited rhythms of the disco scene was swept away by the austere, gray, virile, and metallic rigor of the yuppie era that defined the following decade.

The Thirties-seen-through-the-Seventies era, along with its disco flair, has never truly gone out of style. Musical trends may evolve, but the elegant man remains steadfast: his references have only grown richer. In Paris, a renewed passion for those decades—along with the revival of the styles and figures that defined them—has surged among designers like Husbands, Fratelli Mocchia di Coggiola, Gucci, and, of course, the timeless Ralph Lauren. This enthusiasm is also alive in establishments such as L’Alcazar, the Bonnie Club, Chez Loulou, and the newly opened Les Grands Ducs.

Far from being dreary historical reenactments or banal costume parties, these venues embody an elegant and sentimental lineage of revival. They are a glittering slap in the face to anyone who believed the carefree, camp exuberance of the Seventies was dead. Gentlemen, dust off your pink velvet tuxedos and patent leather boots—it’s about time!

Massimiliano Mocchia di Coggiola is a regular contributor to Sky Blue. His work is published internationally in numerous different works, and he has a published book entitled "Dandysmes" , by Alter Publishing.

Sky Blue

Est. 2019